Social prescribing in Ripon Museums

NHS England has announced that it is creating an ‘army’ of social prescribing link workers to work in primary care as part of the NHS Long Term Plan. Their role will be to connect people with a variety of health needs to alternative non-medical sources of support within their local community.

There is growing evidence of the effectiveness of social prescribing, though we are still a long way from definitive studies. The experience of the town of Frome in Somerset, though, last year hit the headlines with a reduction in the number of emergency hospital admissions by 17% against a rising trend elsewhere in the county. The Compassionate Frome project trained volunteers as Community Connectors to help people to find the right service for them. Community development – and buy-in from GPs – have been key to its success.

I have been working with the Ripon Museum Trust to set up a small project to help people access volunteering opportunities within its museums, which was promoted to GPs as a social prescription. Initially the Culture and Connections project, set up with funding from the University of York ESRC Impact Accelerator Account to embed Connecting People into the work of the charity, this has become Volunteering for the Soul with support from the Coins Foundation.

The scheme supports people to access the multitude of volunteering opportunities provided by Ripon’s museums, which are a key hub within the local community for social connections. Although the evaluation of the project is on-going, an interim analysis has found well-being gains for its participants.

The mental health benefits of volunteering are well-known, but cannot be overstated:

The social gains are less well-evidenced, though you don’t need to look far to find the impact of Connecting People:

While social prescribing can provide benefits for individuals and help reduce demand on the NHS, creating link workers alone is not sufficient.

The Compassionate Frome project was a success as it adhered to the principles and practice of community development. In my experience in Ripon, too, it is important to provide support to those creating new volunteering or community engagement opportunities. The NHS Long Term Plan hopes to support up to a million people via social prescribing, but the voluntary and community sector needs help to manage this influx. Small voluntary and community sector projects cannot be expected to manage people with additional support needs, or a significant number of new volunteers, without a meaningful injection of funding. Social prescribing will not work without community development.

In Ripon we received more referrals from elsewhere in the voluntary sector or from mental health services than from primary care. Frequently, though, the support needs of these people were too high for the project as they required one-to-one support. The enthusiasm for the project sadly underlined the lack of alternatives for some people who did not meet the high thresholds for mental health services or who had few alternatives due to the closure of other voluntary sector services. A significant repair to our voluntary and statutory services is required post-austerity.

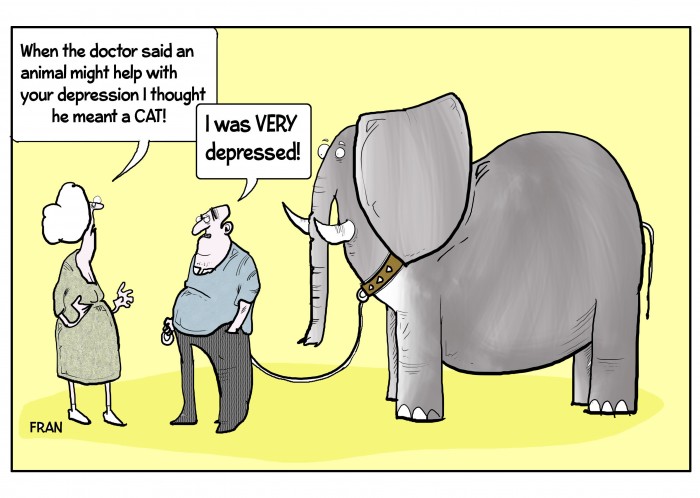

Our experience has also been that social prescribing does not come naturally to GPs. A significant behaviour change will be required in primary care to realise the ambition of the NHS Long-Term Plan. It cannot be assumed that GPs will consider a social alternative to anti-depressants or psychological therapy. This is not just a matter of a lack of randomised controlled trial evidence of the effectiveness of social prescribing; a seismic shift in the mindset of GPs is required.

Referrals to our project in Ripon from GPs have been very slow, and from only half of the surgeries we have engaged with. This perhaps suggests that the scheme is appropriate for only a small number of people – though in a city of 17,000 people one would expect at least a modest number of people to be interested. It may suggest that people require more support than we envisaged to make the first step into engaging with a new volunteering or community opportunity. Or it could be that in spite of the scheme co-ordinator’s frequent attendance at surgery meetings, flyers and letters to the practices, GPs’ referral behaviour is slow to change.

Also, has anyone paused to consider why the NHS is creating another new workforce for this social prescribing role? What training will be provided to link workers? Will they be volunteers as in Frome? Or will they be para-professionals, like the graduate primary care mental health workers were? It would seem obvious that Connecting People provides a core model for their work. I would imagine that they will also be expected to have good local knowledge, effective relationship skills and to take a person-centred approach. These are all core social work skills, but why are social workers not being considered for these roles?

Social workers have the potential to make a meaningful and diverse contribution to primary care. They can provide a link with Children’s Social Care and support health visitors, practice nurses, GPs and others involved in child safeguarding proceedings. They can provide a keyworking role for frequent users of primary care whose needs are predominantly social, though don’t meet the referral criteria for Adult Social Care or any of the other voluntary or statutory sector services. Social workers have the skills to manage the complexity of issues which people bring to their GPs, which either a 10-minute consultation or a social prescription cannot tackle. They are accustomed to working flexibly and developing individualised care and support plans, as required by the NHS Long Term Plan. They can provide additional support to people being discharged from mental health services at an increasingly quick rate because of the high demand for mental health care. They can also connect with local authority Adult Social Care services to arrange Care Act assessments or intervene directly to address loneliness and social isolation.

I could go on, but in all the discussions about the increasing demand for NHS services, social workers have been largely forgotten as their role has become too narrowly conceived as focusing solely on statutory duties. There is an opportunity here to return to more generic community-focused roles which can both support the NHS and help local communities. Link workers will only be able to provide a fraction of what a qualified social worker can do.

To return to the question I pose in the headline, the answer is, of course, ‘it depends what the question is.’ If the question is ‘how do we solve the problems caused by austerity?’, or ‘how do we deal with the rising demand on the NHS?’ then social prescribing isn’t the only solution. It is too narrowly conceived and still couched within a medical paradigm. But it is a nod in the right direction. While much is determined by the direction of public policy, we must find some of the solutions ourselves, within our local communities.

Interesting read and as a community development pracitioner of almost 20 years experience it’s heartening to see CD as an acknowledged factor in Ripon’s success.

I can also testify to experiences as part of the Communities First programme in Wales in Blaenau Gwent – location of some of the UK’s starkest health inequalities – that one can have all the connecting activities and all the innovative/creative social prescriptions available but without the GPs on board then it can count for little. It isn’t just the pace, but the volume of referrals which is critical. A critical mass of referrals creates abundant social capital within the groups involved in whatever activities they are. This in turn raises the capacity of the facilitators/hosts of the social prescriptions to continually-improve and refine their ‘offer’, and creates a pathway towards potential co-production of the prescriptions by the patients themselves.

A CD approach should always look to opportunities to collectivise and organise. We can all do more individually to eat better, exercise more. But there is a persistent, embedded societal trend of individualising poor health and blaming people’s own pathologies for their health challenges. The sytemic problems within our economies, planning regimes and work cultures are significant factors: the abundance of fast food chains in many towns; the increasing unaffordability of leisure opportunities; long work hours; and lengthy, sedantary commutes. These are not just bad for our wasitlines but our mental health. Communities need to increasingly organise themselves in ways that create solutions to these: edible communities; buy local/indie alternatives; challenge lowest common denominator planning decisions; coworking spaces closer to people’s homes and communities; co-operative leisure solutions; utilsiing under-used local assets such as school gymnasiums. All of these have an enabling effect on our individual decision-making about our health.

There is little mention here of the role, current or potential, of practice managers. In my CD career they too have been critical both in terms of connecting and appealing to whom the values of CD, but also as gatekeepers to the GPs who, understandably, are under huge pressures to see and diagnose patients within target times, etc.

Thanks, Russell, for your response and for furthering the discussions of these issues on your blog. I think the role of practice managers is certainly one which we can explore further as the project progresses. Many thanks!