Our research has found that health and social care practitioners can support people to improve the resourcefulness of their social networks. The multi-site pilot of the Connecting People Intervention found that when it was fully implemented it increases

Our research has found that health and social care practitioners can support people to improve the resourcefulness of their social networks. The multi-site pilot of the Connecting People Intervention found that when it was fully implemented it increases mental health and social care service users’ access to social capital.

Background

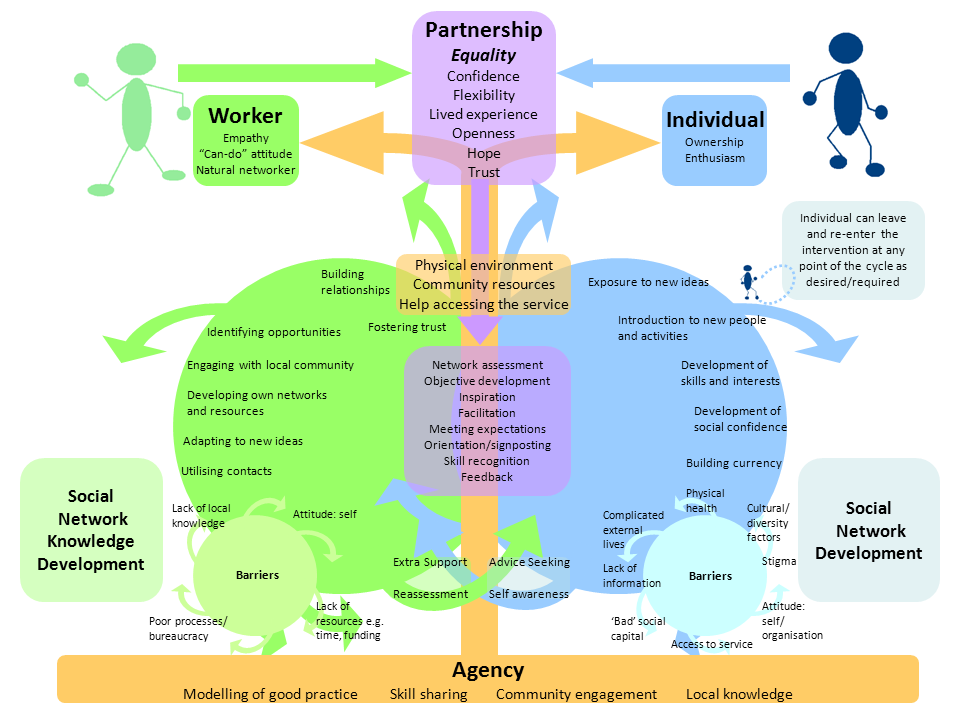

We developed the Connecting People Intervention (CPI) from the findings of a qualitative study of health and social care workers in six statutory and third sector agencies working with people with mental health problems. This initial study found examples of good practice which were modelled into an intervention. This provides guidance to practitioners about how to most effectively support people to enhance their networks.

The CPI requires both workers and service users to engage in a process of discovery. Service users are supported to engage with new social situations and workers are tasked with becoming more familiar with their service users’ communities. This practice is supported by the work of the agency which promotes the development of social connections beyond health and social care services.

In this pilot study we aimed to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the CPI model in services for adults with mental health problems or a learning disability.

Method

The CPI was piloted in 14 agencies from local authorities, the NHS and the third sector across England. We worked closely with participating agencies to support the implementation of the CPI model in their practice. This involved providing comprehensive two-day CPI training and ongoing support throughout the duration of the study.

New referrals to the services were interviewed at baseline (n=155) and nine-month follow-up (n=116), capturing quantitative and qualitative data to evaluate the extent to which the CPI is effective and represents good value for money in helping people to improve their social participation and well-being.

We also selected and interviewed key workers (including supervisors, managers and frontline workers) from each agency (n=39) who provided an informed perspective on the implementation of the CPI in their team or agency. Fidelity to the intervention was evaluated by triangulating responses to a structured interview administered to service users and practitioners with researcher observations of practice within participating agencies.

Findings

We found that people in agencies where the CPI model was implemented more fully had better social outcomes over a nine-month period. Specifically, they had access to more social resources from within their networks, such as advice (e.g. about money problems or employment), information (e.g. about local council services or health and fitness), or practical support (e.g. lending money or help around the house) from the people they knew.

Also, they felt more included in society than those in agencies where the CPI model was only partially implemented. Partial implementation occurred when there was minimal engagement with the services users’ local community; strengths and goals of service users were not fully assessed; or when practitioners were minimally involved in supporting service users to develop and maintain their social relationships, for example.

Service use and the costs associated with this decreased for all participants receiving some level of CPI during the nine-month study period. Additionally, those who were in agencies where the CPI model was implemented more fully had lower costs throughout the study period. These participants also had higher ‘quality-adjusted life-years’, which indicates that the CPI improves outcomes at a lower cost when implemented more fully. However, it is important to note that all but one of the agencies which implemented the CPI more fully were in the third sector, where service costs are lower than in the statutory sector and individuals’ needs are also likely to be different.

The findings indicate that when the CPI model is integrated more fully into social care practice, service users are supported to develop and maintain social relationships with family, friends and members of the local community as appropriate to their needs and wishes. Members of staff who are well-trained, supported and supervised can develop their practice and an agency’s services so that it becomes fully integrated with the CPI model. In the agencies observed to be implementing the model more fully, there was a greater focus on the partnership between workers and service users. This enabled people to form new relationships and support existing relationships with friends and families. Discussions about individual strengths and interests, goal setting, and making plans toward achieving these – all important elements of the CPI model – were more apparent in the agencies which more fully implemented the model.

Most of the staff interviewed for the study responded positively to the CPI model, and in many ways felt that it espoused and validated the work they were already doing. Although some felt they were doing this work, only by implementing the model could better outcomes be achieved, and it was clear that the ethos of the agency influenced the adoption of the model by workers. For the CPI model to be more fully implemented, new ways of working need to be fully embraced by agencies. This requires on-going training, supervision and leadership within agencies, which appeared easier to achieve in the third sector.

The implementation of the CPI model in the local authority and NHS sites was hampered by the lack of work capacity among staff to engage with the model. Their work was affected by performance targets, reconfigurations, public sector funding cuts and the wider austerity environment. If the CPI is to be effective in statutory agencies, workers need to be ‘given permission’ to undertake community-oriented or community development work, and for their job roles to be amended accordingly.

Personalisation can facilitate the process of connecting people, but eligibility thresholds for personal budgets are high, which restricts access to them for many people recovering from mental health problems. It also requires workers to be creative in care planning to consider how needs could be met within communities rather than services.

Many participants in the study lacked money to undertake even inexpensive activities in the community, which presented a significant barrier to their social participation. It is possible that creative use of personal budgets could facilitate this. Also, fundamental needs such as housing were more important for some people than enhancing their social connections. It appears likely that the CPI model works best where people have their fundamental needs met and are financially stable as social participation is not always cost neutral.

Implications

The findings of this study suggest that policy makers, commissioners and senior managers in provider services need to re-orientate social and health care services to be more focused on the communities in which they are located. This is important to support the recovery and social inclusion of people with mental health problems. While this appears to be the intention of many agencies, this study found that statutory services are some way from achieving this goal. Mental health social workers have an important role to play in working with communities as well as individuals (see the College of Social Work position paper for more on this), but statutory services need to re-orient their practice to facilitate this.

Further information

The Connecting People study website has a host of resources including a link to the practice guidance and training videos. A fuller summary of the research findings and list of relevant papers can be downloaded here.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the NIHR School for Social Care Research. The views expressed in this blog are mine and not necessarily those of the NIHR School for Social Care Research or the Department of Health, NIHR or NHS. I would like to gratefully acknowledge the time given by the participants in this study and would like to thank their agencies for providing us with access to their expertise. I am also indebted to my colleagues David Morris & Sharon Howarth (University of Central Lancashire), Meredith Newlin & Sharon Howarth (University of York) and Paul McCrone (King’s College London) who worked on this study with me.

One thought on “Connecting People Intervention improves network resourcefulness”