The findings of the Community Health Network study were published this week by Health Services and Delivery Research. Led by Vanessa Pinfold of the McPin Foundation, this study investigated how social contacts, meaningful activities and places that

The findings of the Community Health Network study were published this week by Health Services and Delivery Research. Led by Vanessa Pinfold of the McPin Foundation, this study investigated how social contacts, meaningful activities and places that people with mental health problems had connections with were utilised to benefit health and well-being. We examined what happened in people’s lives using a network-mapping technique; how community assets were used to support recovery; and the influence of primary care and secondary mental health practitioners in personal networks.

Aims

The study aimed to understand the personal networks of people living with a mental health problem from their own perspective. We were also interested in how personal well-being was supported by the exchange of resources so that we could better understand how individuals’ networks could be supported by practitioners and mental health providers.

Methods

The study had five components:

- 30 in-depth interviews with organisation leads to understand the local service and policy context for supporting people with mental health problems in the two study sites

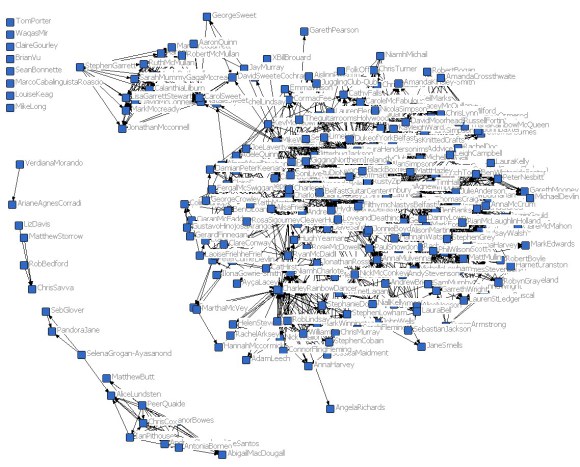

- Network mapping of 150 people with mental health problems to collect personal network data on people, places and activities as well as measures of social capital, well-being and health functioning

- 41 in-depth follow-up interviews to explore how people with mental health problems managed and developed their connections over time

- 44 telephone interviews with GPs, psychiatrists, care co-ordinators and third-sector staff to understand their role in facilitating growth of social, activity and place connections

- 12 in-depth interviews with stakeholder leaders in primary care, commissioning and mental health service delivery organisations to share study findings and gain policy updates.

The study was conducted in a London borough and a county in south-west England.

Main findings

Three types of personal networks were found:

- Diverse and active networks had higher numbers of people, place and activity connections. Those with these networks had the highest proportions of new connections and highest network satisfaction. Qualitative analysis found active management of connections, resources and network opportunities, but that big was not always better. Diversity and variety could be associated with enhanced personal well-being and more durable networks, but for some people connectedness caused stress and distress. Manageable routines were important and stigma featured prominently; as networks diversified, the potential for mental health discrimination increased.

- Family and stable networks had the highest access to social capital and health resources, but lower levels of activity and place connection than diverse and active networks. Participants with these networks spent most of their time at home but tended to live with others. Qualitative analysis found high levels of social support and building blocks for wellness and recovery through family connections; however, such support could also restrict access to wider social capital and well-being resources. Reciprocal relationships were highly valued.

- Formal and sparse networks were significantly smaller with lower access to social capital and health resources, poorer functioning and well-being. They were the least active, having fewer friends, family and wider contacts, and practitioner contacts were more dominant. Qualitative analysis found mental health problems featured most strongly in these networks framing decisions and experiences. We found agency in some of these networks, despite limited resources, and potential building blocks for recovery; others needed help identifying potential opportunities. Formal and sparse networks were sometimes considered beneficial for supporting individual well-being. These networks also revealed the resentment that some people feel when relying on practitioners to support mental health and well-being.

Social capital was mostly accessed through family and friends, with practitioners generally having a more limited role, although practitioners were more prominent in networks lacking informal social support. Connections to activities, including employment, and places were important, as they were gateways to social ties. Our study participants had access to lower social capital than the general population.

We found individual agency across all network types and surfaced tensions, including relationships with practitioners or families; dealing with the impact of stigma; employment and financial frustrations. The value of connectedness in countering the risk of isolation and loneliness within personal networks and supporting recovery was evident. Connectedness shapes identity, providing meaning to life and sense of belonging, gaining access to new resources, structuring routines, helping individuals ‘move on’ in their recovery journey.

Mental health and primary care services appeared to thwart the agency of practitioners, creating obstacles to person-centred outcome-focused care, even within the third sector, where people wanted to work in this way but were restricted by commissioning arrangements. Developing the personal networks of individuals with SMI was not an organisational priority in the way that management of symptoms, medication and risk was. As long as this remains the case, it seems unlikely that these people will be able to build personal networks that make use of the full potential of their inner and external resources.

Implications for practice

There is a need for improved organisational collaboration. Several service ‘silos’ were in operation and we found there was a significant community resource knowledge gap; many practitioners rely on their own interests and professional networks to learn about community opportunities to support clients. A system that could encourage interorganisational community information sharing, and ideally practitioner and service use feedback on the value of local resources, is recommended.

Meaning and direction must come from people with mental health problems themselves, but practitioners have a vital connection-building role, in part by showing that networks and the resources within them matter to recovery, alongside medication and psychological therapies. Organisations also have a key role to play and, in times of change or restructuring, this includes planning how changes in community resource levels might impact on people with mental health problems.

Skilled care co-ordinators acknowledge the importance of network development, but need support to make it a larger part of their role. Creating shared care processes with primary care and the third sector will become fundamental in the management of severe mental health problems; being alert to the importance of connectedness through people, places and activities should feature in care planning.

A crucial gap in practice was the lack of any overarching framework for the provision of services to people with mental health problems following a recovery approach. Social outcomes of care are largely absent in the current NHS outcomes framework which applies only to secondary care. Building a set of social outcome indicators for mental health problems and including network indicators that operate across service silos would incentivise joint working and promote social inclusion.

Final report

The final report is available open-access in the Health Services and Delivery Research Journal. The full-text PDF can be downloaded here free of charge.