The use of the Mental Health Act 1983 in England has increased considerably between 1984 and 2016. A new analysis of this trend has been published in the October edition of the British Journal of

The use of the Mental Health Act 1983 in England has increased considerably between 1984 and 2016. A new analysis of this trend has been published in the October edition of the British Journal of Psychiatry by Patrick Keown and colleagues1. They have largely attributed this trend to the move to community-based mental health services, but their analysis omits a critique of changes in Government and the consequences of austerity.

Increased detentions

The healthmania news reported that the rate of detentions (not including court orders and prison transfers) of more than 3 days increased from 21.5 per 100,000 population in England in 1984 to 85.0 in 2015/16. The rate of detentions following a voluntary admission increased from 17.5 in 1988 to 30.7 in 2015/16. The overall rate of detentions increased from 50.0 per 100,000 in 1988 to 115.7 in 2015/16. The rates of forensic detentions were negligible in contrast, at between 3.0 and 4.5 per 100,000 over the corresponding time. There has also been a dramatic increase in the use of private hospitals for compulsory admissions. In 1984, only 3% of detentions were made to private hospitals, but this increased to 15% by 2015/16. The reduction in NHS beds has proved a false economy, as the full cost of expensive private beds is passed on to the NHS.

In addition to the reduction in beds, the authors proposed six additional explanations for the increase in the rate of detention:

- Accepting more referrals from primary care has increased the accessibility of mental health services, leading to better ‘case identification’. I’m not entirely convinced by this argument. If mental health services were more accessible (which I don’t accept they are) then support could be provided to people earlier, thus preventing mental health crises and the need for compulsory admission to hospital.

- The improvement in community services has resulted in better follow-up. Similarly, I’m sceptical about this argument. If community services were better, then improved community care should be able to support people in mental health crisis at home rather than requiring compulsory admission increasingly frequently.

- Clinicians detain people in hospital to improve outcomes by using interventions they cannot deliver safely in the community. As above, if community services were robust, then community treatment should be as safe and as effective as in hospital.

- Clinicians use the Mental Health Act to manage risk. This explanation is one which I do agree with. There is considerable evidence that mental health services have become more risk averse and compulsion is used to avoid the potential for harm to occur.

- The introduction of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 and changes to the Mental Health Act in 2007 led to increased detentions. It is true that people who previously lacked capacity to object to being in hospital became subject to detention, but the number this applied to was relatively small and could not account for the dramatic increase in the rates of detentions.

- I cite the final explanation which Keown et al provide in full, so you can see that the words are theirs, not mine: “Teams have been developed by many Social Services Departments, whose sole purpose is assessing, and if appropriate, detaining, patients under the Mental Health Act. These are staffed by social workers, who previously would have had case-loads, and have engaged in preventive work in addition to their role in detaining patients.” (p.598)

There are many aspects of this latter argument which I have a problem with. Firstly, they imply that detentions have increased because there are teams dedicated to assessing people under the Mental Health Act 1983, as if they were conspiring together to detain as many people as possible.

Secondly, yes, they are ‘staffed by social workers’, but in their role as Approved Mental Health Professionals (AMHPs). AMHPs have a duty to assess people for admission to hospital under the Mental Health Act 1983 and make the application for detention if it is required. Local authorities are increasingly removing mental health social workers out of NHS mental health trusts as a consequence of their significant budget cuts. Local authorities have a duty to provide a sufficient number of AMHPs in their areas. However, as their budgets have shrunk, their ability to employ AMHPs, and second them to undertake care co-ordination roles in NHS community mental health teams, has significantly reduced. Some local authorities, whose budgets have been pared to the bone, have been forced to require their social work AMHPs to only undertake assessments under the Mental Health Act 1983 and thus no ‘preventive work’. The singling out of social workers for mention here is a little unfair as other mental health professionals, such as nurses and occupational therapists, are also AMHPs.

Thirdly, NHS community mental health teams have largely replaced the social workers who have been withdrawn from their teams with nurses or with social workers whom they directly employ, so the net loss of the AMHPs is not as significant as Keown et al suggested. In all areas, social workers and AMHPs are a very small component of the community mental health workforce overall.

Other explanations for the increase in detentions

I would like to offer some additional potential explanations for the increase in detentions since 1984.

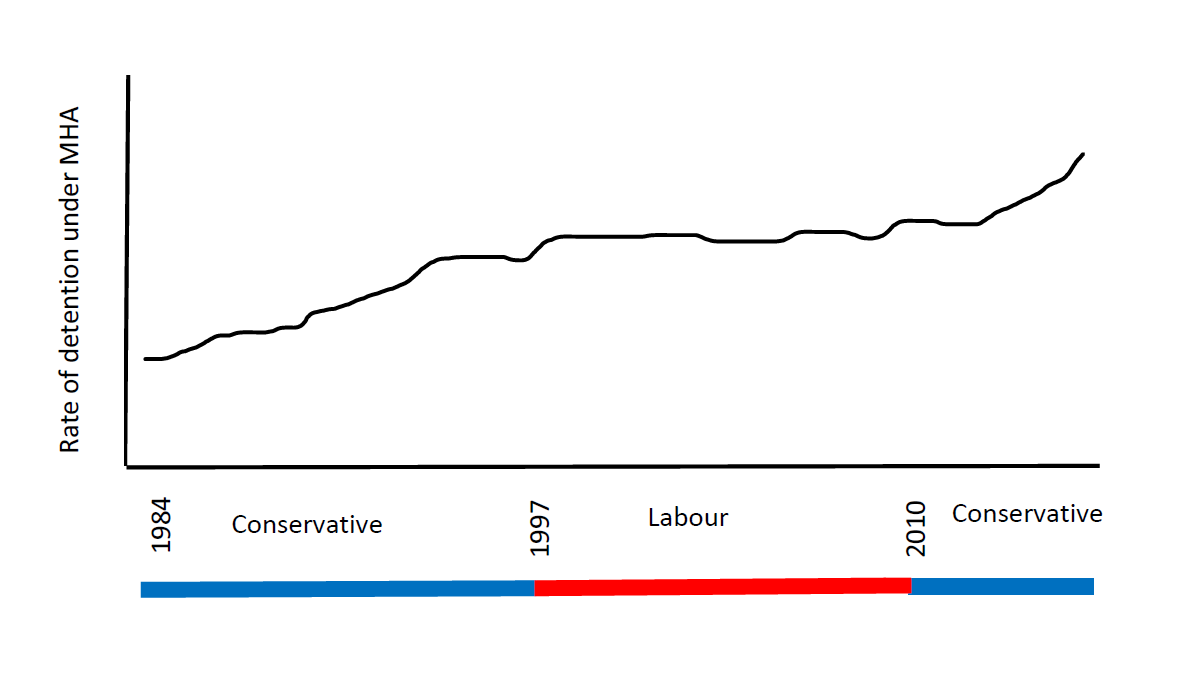

Keown et al produced a chart showing the increased rate of detentions. It showed a clear increase in overall detentions until 1998, at which point they level out. From 1998 to 2010 the rate of detentions remains relatively stable, with no significant increases. However, they rise again after 2010, at an increasingly steep rate. The increase in detentions is very closely related to periods of Conservative Government before 1997 and after 2010 (see below). I would suggest that increased public spending during the years of Labour Government had the effect of arresting the increase in the rate of detentions.

Increased investment in mental health services under the Labour Government saw the introduction of assertive outreach teams and crisis resolution and home treatment teams in every area of England and Wales. These provided more opportunities to work with people in crisis in their homes. The National Service Framework, introduced in 2000, aimed to reduce the postcode lottery of mental health services. But this returned after 2010 when David Cameron’s focus on localism saw a patchwork of locally-determined services making a comeback.

The organisation of secondary mental health services has become dominated by the system of Payment by Results and Care Clustering, in which people are grouped largely according to their diagnosis, and offered a specific menu of interventions. Throughput through secondary mental health services and back to primary care is encouraged, in order to trigger payments and to free up space for people waiting for the service. The quick discharge of people back to primary care, where there is minimal support for their mental health, has increased the risk of relapse, mental health crises and subsequent detentions under the Mental Health Act.

Periods of Conservative Government are associated with increases in poverty and inequality, both of which increase the risk of mental health problems. Levels of personal debt are currently at an all-time high and it is well-known that suicide is now the leading cause of death for men under the age of 45. Although unemployment is currently very low, it has been replaced by an increasing number of insecure poorly-paid jobs and a decimated system of welfare support. The rise of homelessness and food banks across the country since 2010, particularly in areas trialling Universal Credit, are visible signs of the impact of austerity. The social determinants of mental health and the socio-eoconomic environment in which people are living cannot be ignored when exploring reasons for an increase in detentions under the Mental Health Act.

Detentions are required when people do not want to go in to hospital voluntarily. Many people assessed under the Mental Health Act have prior experience of treatment in mental health services. If their previous experiences of treatment – at home or in hospital – were more positive, it is possible that more people would accept treatment at home or a voluntary admission to hospital. The harmful side-effects of many psychiatric medications could be one reason why people do not wish to accept treatment for their mental health problems.

The role of the AMHP – which Keown et al do not refer to in their paper – is to consider the least restrictive alternative to hospital. The purpose of having an AMHP conduct an assessment (in most other countries it is purely a judicial procedure) is to consider alternatives to hospital admission. This has become increasingly difficult when alternatives have been lost to austerity. Crisis houses or therapeutic communities, for example, have either closed down or restricted their eligibility criteria to such as extent that they are rarely available as a realistic option in a mental health crisis.

In addition, mainstream community services which help to provide social connections and build communities, have closed at an alarming rate since 2010. The cuts in funding for youth services, libraries and community centres, for example, in combination with the closure of mental health day services, has drastically restricted the opportunities for individuals to seek support beyond their immediate family. Also, less community support places increased stress on families, which decreases their ability to cope with family members in a mental health crisis.

Increasing rates of mental health problems, and no corresponding increase in Government funding for mental health services, has meant an increase in their eligibility thresholds. It is increasingly difficult to be seen by a mental health professional, unless you are acutely unwell, at risk to yourself or other people, and in high need of mental health support. The lack of lower-level support has meant that people are often only seen when they are in a crisis. However, the reduction in beds has meant that detention under the Mental Health Act is often the only way to provide them with access to mental health treatment, as a bed has to be found for them (hence the increase in the use of private beds).

The immense pressure mental health services are facing has led to many community mental health teams discharging people if they miss two or more appointments. There are many reasons why people may find it difficult to attend appointments, not least because of their socio-economic circumstances or mental health problem. Discharging people to create space for new referrals pushes people into a cycle of relapse and mental health crisis, and a detention under the Mental Health Act is often the only way to secure access to mental health treatment.

Mental health services need to be properly funded so that they can support people over a longer period of time and not just when they are in crisis. They need to be fully engaged with the communities in which they are located, which themselves require better resources and accessible support. They also need to be freed from the hegemony of the medical model, which requires detention in hospital if medication cannot be given at home. One only needs to look to countries like Finland, where using Open Dialogue keeps people experiencing psychosis at home and off medication, to believe that there can be a different approach to providing mental health services.

Reforming the Mental Health Act will not stop the increase in the number of detentions, but reforming mental health services might do. But that will take a change in Government to achieve.

1 Keown, P., Murphy, H., McKenna, D. & McKinnon, I. (2018) Changes in the use of the Mental Health Act 1983 in England 1984/85 to 2015/16, The British Journal of Psychiatry, 213, 595-599.

Thank you for your analysis. I would like to add some thoughts.

I think your suggestion that austerity and poor levels of funding of mental health services is an important cause is somewhat consistent with evidence. Presumably the mechanism would be that more people are ill and/or that severity of illness is worse, and community services are less less to treat people effectively than they were under labour (pre-crash) due to funding pressures, so more people are being treated involuntarily in hospital. Is that correct?

The numbers of people (per 100,000 population) in contact with the secondary MH services has risen in recent years, consistent with your suggestion. However, fewer people (per 100,000) are being admitted (based on mental health bulletin data) to psychiatric hospital. Based on mental health act statistics, the number of uses of the MHA (per 100,000 population) has risen. But based on MH bulletin data, the number of people in contact with the secondary MH services and who were detained last year (again per 100,000 population) has been fairly flat in the last 10 years – if anything in slight decline. The proportion of people being admitted informally has fallen dramatically, which is consistent with staff managing risk/liability, so the proportion of formal admissions has risen significantly. Of course, there is reason to think that more people are ill, and severity of illness may

be worse. But admission figures are not particularly consistent with community facilities being substantially less able to treat patients in the community leading to more hospitalisations, at least superficially.

Of course all this is in the context of the number of inpatient beds in psychiatric hospitals per 100,000 falling (and there has been a slight rise in the use of private hospitals as there isn’t enough space in NHS ones). Therefore a decline in admissions may merely reflect a lack of beds. This would be consistent with the explanation that increasingly patients are being admitted formally in order to secure a bed. However, it isn’t clear to what extent such practice is growing. Keown et al. in a previous paper demonstrated an association between a drop in bed numbers and rising uses of the MH act.

Importantly, the rise in the uses of the MHA is mostly in section 2’s on admission. Section 3’s on admission (per 100,000 pop) have been flat or slightly declining. However, conversions from s.2 to s.3 has been rising. Overall, I think this indicates that people aren’t being admitted, at least at first, in order to receive treatment that they have so far refused. Instead, increasingly patients are being admitted formally on s.2 instead of being admitted informally. This points to a change in the clinical culture around admissions I think, and medics mitigating risk or looking to secure a bed or something similar. .

Although difficult to find precisely, based on NHS reference costs, it looks like spending on MH services has risen above inflation recently. But because many more people are in contact with the secondary MH services, spending per person in contact with secondary MH services has fallen. This certainly points to services being less able to cope. However, spending figures may well fail to reflect increasing (perhaps structural) problems faced by the MH services that limit the ability to treat patients.

I think the data at this stage are most consistent with hospital treatment being used less and less (in terms of the proportion of patients being treated in hospital each year), but that the proportion of admitted patients being admitted formally is rising. This may suggest that, increasingly, only the illest patients are being admitted – perhaps consistent with the mechanism you suggest. But this is difficult to identify using readily available data. And/or it perhaps reflects a change in the typically path for patients being admitted – patients increasingly are being admitted formally to minimise legal risk, to secure a bed, or perhaps because (another suggestion by in the literature) patients don’t want to be treated in hospital because wards are traumatic/untherapeutic, poorly funded etc.